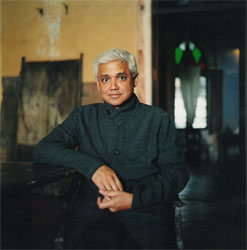

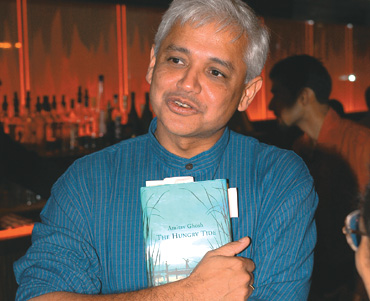

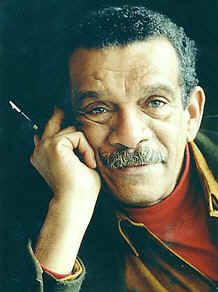

Kancha Ilaiah is a fascinating thinker and writer. He first made waves with his book Why I am not a Hindu. Parts of that book even appeared in the famed Subaltern Studies. He has to be credited for his concept of ‘dalitization’ which is a very useful sociological concept. He is often difficult to agree with, as his ideas take liberty with facts referred to. But, his works always will provide you insights that are uncommon. He is provocative. Ilaiah is a must read. Here is a review of his new book by Anand Teltumbde, which appeared in Tehelka. Although Teltumbde is critical of this book, you will notice he admits to Ilaiah’s strength of observation. Teltumbde is a fine thinker too. Check out the review.

KANCHA ILAIAH is known for books with explosive titles like Why I Am Not a Hindu and Buffalo Nationalism, but with spiritual content. This book, his latest, follows in the same tradition. At a time when many intellectuals are morbidly worried about the resurgence of Hindutva, Ilaiah boldly sees Hinduism on course of its death because of its “failure to mediate between scientific thought and spiritual thought”. The book is a reflective account of his own journey through castes and communities and highlights everyday clashes of caste cultures and conflict between “the productive ethic of Dalit-Bahujan castes and the anti-productive and anti-scientific ethic of Hindu Brahminism”.

The contents page would catch the fancy of any reader with its catchy phrases like ‘intellectual goondas”, “spiritual fascists”, used for Brahmins and “subaltern scientists”, “meat and milk economists” for the Dalit- Bahujans. The first thing that crossed my mind is that the marketing wing of any publication house will be simply overjoyed with brand ‘Kancha Ilaiah,’ with its potential appeal to the vast market spanning three out of four spiritual worlds (Christian, Islam and Buddhist, excluding Hindu), to make use of his phraseology. Indeed, with his passionate promotion of Dalit-Bahujan and outlandish interpretation of mundane details of life, he has created a unique place for himself among subaltern writers.

POST-HINDU INDIA: DALIT-BAHUJAN SOCIO-SPIRITUAL AND SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION

Kancha Ilaiah

Sage Publications

316 pp; Rs 295Reading this book gives you a feel of travelling in a Maglev train — an illusion of running on rails but in fact levitates over a thin layer of air. While traversing through its arguments, the book creates an illusion of being based on truth but is distanced from it by a thin layer of prejudice. There is an overdose of culture and spirituality which could intoxicate readers without them realising it.

If one is not so ‘spiritually’ intoxicated, one suffers from mundane doubts nibbling at his intellect: is this conjoint term ‘Dalit-Bahujan’ sociologically viable, given the huge load of material contradictions between these two population groups that have been precipitating into most heinous caste atrocities? How and why did these worthy ‘spiritual democrats’ or ‘spiritual revolutionaries’ come to emulate the caste hierarchy of Brahmins, the spiritual fascists, within themselves and zealously preserve it? If the Dalit- Bahujans were so accomplished in terms of their scientific and technological prowess, how could they be enslaved by a handful of scheming and spiritually degenerate Brahmins for millennia? The book succeeds in establishing the superiority of Dalit-Bahujans, but doesn’t it essentially follow the very same Brahmanic ethos of superiority-inferiority?

The value of Kancha Iliah’s book lies not so much in its thesis but in the richness of its observations not only on the castes of India, but also on the many people and events in the world.

(Image of Ilaiah and the book are from Tehelka.com)

translations,, two noted works are his translations of Tuka in Says Tuka and his translations of the Marathi Dalit poet Namdeo Dhasal. Tehelka had published an interview with Chitre about Dhasal in 2007. The interview was conducted by S Anand of navayana. Read the complete interview

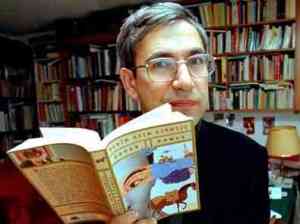

translations,, two noted works are his translations of Tuka in Says Tuka and his translations of the Marathi Dalit poet Namdeo Dhasal. Tehelka had published an interview with Chitre about Dhasal in 2007. The interview was conducted by S Anand of navayana. Read the complete interview  Orhan Pamuk, the Turkish writer, I think is a major writer of our times. The sense of complex texture he brings to his writing is amazing. A book like Istanbul is remarkable both for the rich kernel as for the fine fabric that it is woven in. He takes us in circles: book about book, book within book, story of story etc. His Nobel lecture is very interesting too and again it is a writing about writing. He compares writing to digging (reminds one of Heaney) a well with a needle. Read more

Orhan Pamuk, the Turkish writer, I think is a major writer of our times. The sense of complex texture he brings to his writing is amazing. A book like Istanbul is remarkable both for the rich kernel as for the fine fabric that it is woven in. He takes us in circles: book about book, book within book, story of story etc. His Nobel lecture is very interesting too and again it is a writing about writing. He compares writing to digging (reminds one of Heaney) a well with a needle. Read more